Andrade, J (2010), What does doodling do? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(1): 100–6

Psychology Being Investigated

Dual-Task Performance – This theory focuses on how people manage two tasks simultaneously. The study explores whether a simple secondary task (doodling) could improve performance on a primary task (listening to a monotonous message) by preventing the mind from wandering.

Cognitive Load Theory – This theory posits that working memory has limited capacity. Doodling could theoretically help by occupying only a small amount of cognitive load, thereby preventing the mind from engaging in more demanding distractions that could more significantly detract from the primary task.

Daydreaming and Mind Wandering – Theories around daydreaming suggest that when a task is not fully engaging, the mind tends to wander, leading to decreased attention and memory performance. The study investigates whether doodling can anchor attention and reduce mind wandering during a boring task.

Attentional Resource Theory – This theory suggests that humans have a limited pool of cognitive resources for processing information. Doodling might act as a minimal attentional anchor, helping maintain a baseline level of engagement without significantly taxing these cognitive resources.

Background

Previous research by Do & Schallert (2004) explored how certain activities might aid concentration, particularly in the context of performing primary tasks.

Wilson & Korn (2007) focused on how secondary tasks could maintain arousal levels during primary task performance. This work suggests that engagement in a secondary task might prevent the decrease in arousal often associated with monotonous activities, thereby potentially enhancing performance on the primary task.

According to Harris (2000), boredom is a very common experience, and Smallwood & Schooler (2006) noted that daydreaming is a frequent response to boredom, even in controlled laboratory settings. This line of research indicates that when individuals are not fully engaged in a task, their minds tend to wander, which can negatively affect their performance on the task.

Aim

To investigate whether doodling improves or hinders attention to a primary task.

Procedure

Participants and Sampling

- The study included 40 participants from the MRC Applied Psychology Unit participant panel, recruited from the general population, aged between 18 and 55 years. Participants received a small honorarium.

- They were divided into two groups: 20 in the control group (including 2 males) and 20 in the doodling group (including 3 males).

Procedure

- Participants were recruited after finishing an unrelated experiment, enhancing the boredom factor by testing individuals already thinking about going home.

- They were tested individually in a quiet and visually dull room.

- The task involved listening to a monotonous mock telephone message about a party, including names of attendees and non-attendees, and place names, along with irrelevant material.

- The control group wrote down the names of people definitely or probably coming to the party on lined paper.

- The doodling group shaded in printed shapes (squares and circles) on a response sheet while listening. The task was designed to be simple, encouraging a degree of absent-mindedness akin to naturalistic doodling.

Materials

- The telephone message was recorded in a monotone voice and played at a comfortable volume. It included specific names and place names amidst irrelevant information.

- The doodling group used a piece of A4 paper with printed shapes and a margin for writing down target information.

Task Instructions

- Participants were instructed to write down the names of people who would be attending the party and to ignore those who couldn’t come.

- In the doodling condition, participants were told to shade shapes without concern for neatness or speed, as a way to alleviate boredom.

Data Collection and Analysis

- After listening to the 2.5-minute tape, response sheets were collected.

- Participants engaged in a conversation for a minute, including a disclosure about the upcoming memory test.

- They were then asked to recall names of party-goers and places, with the order of recall counterbalanced across participants.

Measured and Manipulated Variables

Manipulated variable – The primary manipulated variable was the doodling task.

Measured variables – Measured variables included the accuracy of information monitored (names written down) and recalled (names and places).

Results

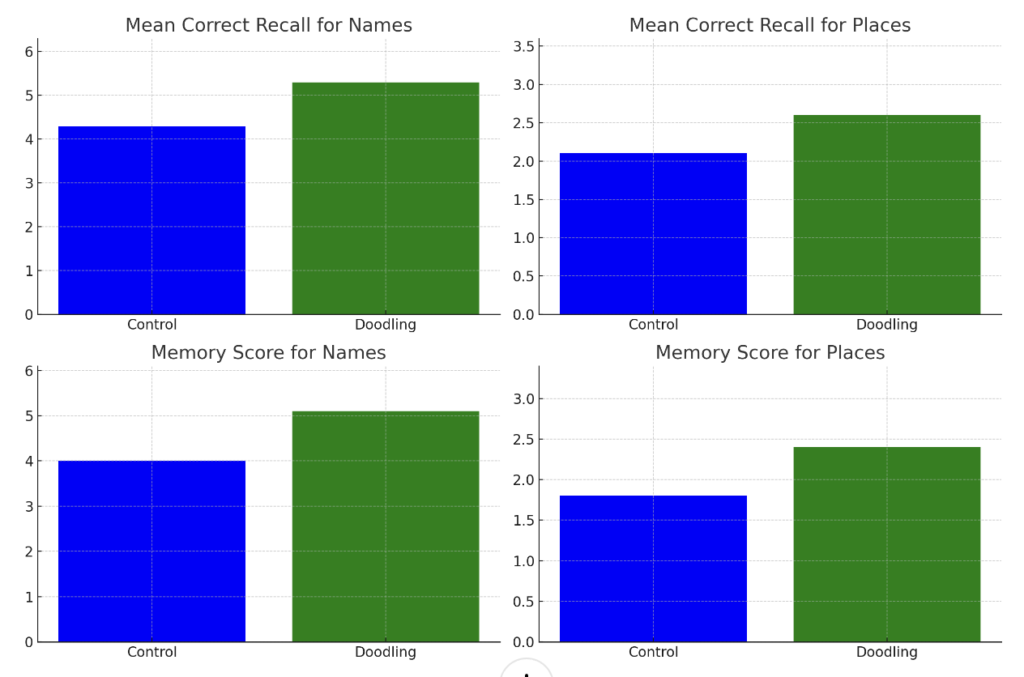

Monitoring Performance

- Control participants correctly wrote down an average of 7.1 names of party-goers during the tape, with some making false alarms.

- Doodling participants had a slightly higher average of correctly written names (7.8) with fewer false alarms.

Memory Test Results

- On average, participants in the doodling condition recalled 7.5 pieces of information (names and places), which was 29% more than the control group.

- In terms of memory scores (correct minus false alarms):

- For names (monitored information), the control group scored 4.0, and the doodling group scored 5.1.

- For places (incidental information), the control group scored 1.8, and the doodling group scored 2.4.

Interpretation of Results

- The doodling group showed better concentration and memory performance than the control group.

- It’s not definitively clear whether the improved recall was due to better monitoring (noticing more names) or because doodling aided memory directly by encouraging deeper processing of the material.

- Overall, the study suggests that engaging in a simple task like doodling during a monotonous task can enhance both concentration and memory recall.

Conclusions

Enhanced Concentration and Memory – Participants who engaged in a shape-shading task (an analogue of naturalistic doodling) demonstrated better concentration on a monotonous mock telephone message compared to those who listened without any concurrent task. This improvement was evident in both monitoring performance and in scores on a surprise memory test.

Unclear Mechanism – While it was evident that the doodling group recalled information more effectively, the study could not definitively conclude whether this was because doodlers noticed more target names (better monitoring) or because doodling aided memory directly by encouraging deeper processing of the material. The exact mechanism of how doodling benefits cognitive performance remains open to interpretation.

Strengths

Ecological Validity – The study was designed to mimic real-life scenarios where individuals might engage in doodling, such as listening to a monotonous phone message. This enhances the ecological validity of the research, making the findings more applicable to everyday situations where people might doodle to alleviate boredom or maintain focus.

Random Assignment of Participants – The participants were randomly assigned to either the control or the doodling group. This randomization helps to reduce biases and confounding variables, ensuring that any differences in performance between the groups can be more confidently attributed to the effect of the doodling task.

Controlled Experimental Conditions – The study was conducted in a quiet and visually dull room to minimize distractions and external variables that could influence the participants’ performance. Such control ensures a high level of internal validity, as it reduces the likelihood that external factors influenced the results.

Weaknesses

Lack of Measurement for Daydreaming – The study did not include any direct measure of daydreaming. This is a significant limitation because the hypothesis was that doodling might affect memory and attention by reducing daydreaming. Without measuring daydreaming directly, it’s difficult to confirm whether this was the mechanism behind the observed effects.

Limited Understanding of the Underlying Mechanism – The study was unable to conclusively determine the cognitive processes behind the observed benefits of doodling. While it provided evidence that doodling aids concentration and memory, the specific cognitive mechanisms – whether it’s by reducing daydreaming, occupying minimal cognitive resources, or some other process – remain unclear.

Generalisability of Results – The study used a very specific type of doodling (shading printed shapes) which might not accurately represent the range of doodling activities people engage in naturally. This raises questions about the generalizability of the results to different forms of doodling or to more naturalistic settings outside the controlled environment of the study.